Sustainable intensification practices―a ray of hope for Zambian farmers facing drought

Smallholder farmers in eastern Zambia, whose livelihoods are heavily dependent on rain-fed agriculture, have been increasingly exposed to rising intensity and frequency of El-Niño induced droughts. Recurrent droughts have escalated over the past 35 years with serious droughts in 1982/83, 1991/92, 1993/92, 1997/98, 2002/03, 2004/05, 2007/08, and 2015/16. Erratic rains and prolonged dry spells have adversely affected agricultural production and sustainability of rural livelihoods in those years.

The 2015/16 El Niño-induced drought is predicted to reduce maize yield by more than 40% in eastern Zambia, with the valley areas heavily affected. High levels of poverty among smallholder farmers (78%), insufficient resilience, economic diversification, and investment initiatives leave farmers vulnerable to these climate shocks. Predicted increases in intensity and frequency of droughts are likely to exacerbate climate-induced economic shock in the next decades, pushing farmers into a vicious cycle of poverty.

The socioeconomic team under the Africa RISING Project carried out a study to understand smallholder farmers’ perception of El-Niño-induced droughts, their impacts on their socioeconomic activities, and their adaptation strategies at the household level. In this study, adaptive capacity is defined as the ability of a system to adjust to climate shocks (including prolonged in-season droughts and shorter growing seasons < 100 days), to moderate potential damages, to take advantage of opportunities or to cope with the consequences. The adaptive capacity of communities depends on many factors such as a) household resource endowments; b) strong social network; c) climate-resilient farming technologies; d) access to inputs; e) knowledge of climate risk; d) agricultural extension services; f) rural financial markets; and g) marketing and storage systems. Although Zambia has an early warning system, forecasting institutions are inadequately equipped and communication to extension officers and farmers in user-friendly formats is limited.

Using participatory rural appraisal (PRA) tools such as trend analysis, and hazard and vulnerability mapping, the study team profiled the climatic context of farmers for the past 35 years (e.g., rainfall and temperature changes, hazard profiles, and community risk analysis). The key emphasis was on the years when there was a poor onset of rains, early termination of the season, poorly distributed and erratic rain, and excessive rain. The PRAs captured existing perceptions of climate change and adaptation measures that are already used and feasible to attenuate the impact from six Africa RISING communities that are representative of the diversity of dynamics in eastern Zambia.

Using descriptive analysis, the PRA qualitative and quantitative findings were consolidated using protocols and summary matrices. Overall, all the communities perceived that the rainfall pattern had changed considerably compared to 15 years ago. For communities in Chipata District, the growing seasons have become shorter, characterized by late onset and early termination of the season and a prolonged dry spell. In the low altitude and low rainfall parts of eastern Zambia (e.g., Lundazi District) the length of the growing season has not changed but the rainfall has become more unevenly distributed in the past five seasons with either more rainfall at the start or end of the season. For Sinda District, communities have observed significant changes in the distribution of the rainfall with more frequent early and mid-season dry spells.

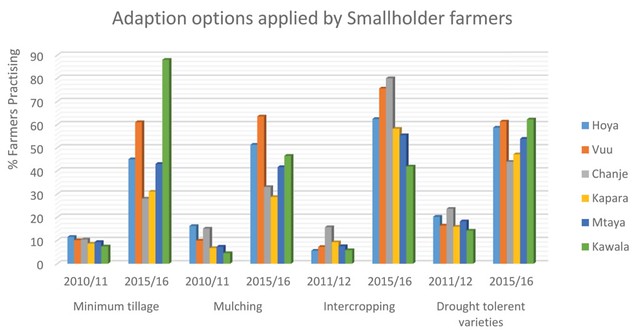

The PRA findings from the three districts revealed that smallholder farmers use agricultural technology innovations and diversification strategies to manage droughts and enhance their resilience to climate shocks. Communities in Lundazi use a combination of ex-ante coping strategies, which include drought-tolerant varieties of different maturity groups, diversity of tillage systems and cropping patterns, staggered planting, and micro-dosing of fertilizers. Increased yields and income from a combination of ripped maize-cowpea intercropping, drought-tolerant maize varieties such as PAN53 and SC633, and incorporation of sunflower to the more common maize-legume cropping system in the 2014/15 season resulted in spontaneous adoption of these technologies in the 2015/16 season.

Similarly in Kawalala Camp, Sinda District, increased yield and income from ripped maize-soybean rotations in the 2014/15 cropping season achieved spontaneous diffusion of these technologies in the 2015/16 season.

The farmers reported an adoption rate of more than 80%. It was however noted that those who did not adopt had limited access to ripping―either they did not have access to animal traction or no money to pay for the services. The income from crop sales was invested in livestock, mainly cattle, further enhancing their resilience in both districts. Crop, variety, and spatial diversification were the commonly used drought management strategies used in Chipata District.

Growing of more than four maize varieties in three different locations (homestead, dambo, and main field) and at least two cash crops (soybean, tomato, tobacco, common bean) have become an integral component of their farming system.

By Munyaradzi Mutenje, Angeline Mujeyi, Mulundu Mwila and Mully Phiri

Originally produced in August 2016